His job is to measure the world precisely:

nothing on his map except what’s actually there—

Bill Meissner, The Mapmaker and His Woman

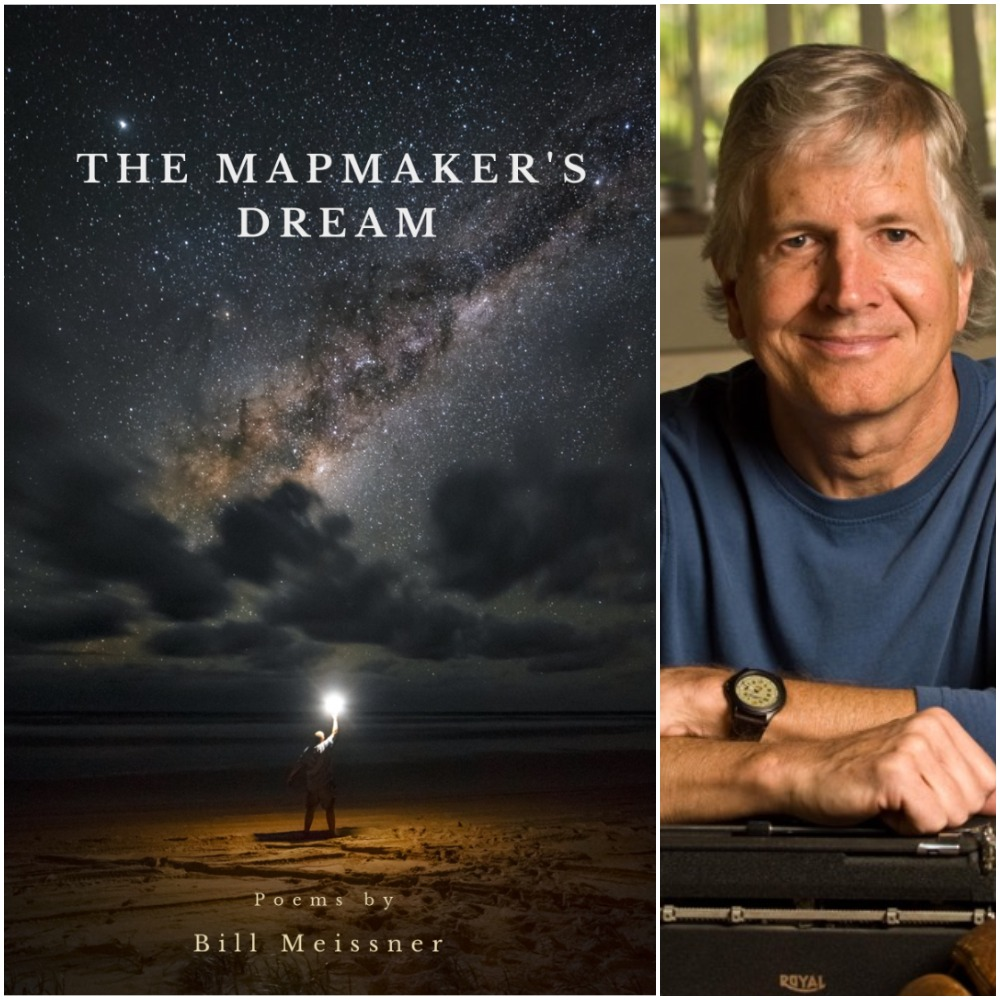

In September, 2019, I met poet Bill Meissner at Jules Bistro in St. Cloud, to talk about his latest book, The Mapmaker’s Dream, and about poetry. Surrounded by echos of strangers’ conversations and the clatter of dishes, he tells me that poetry is a unique way of looking at the world.

“The first time I ever wrote anything,” he says, “I was listening to Simon and Garfunkel songs that were poetic, like “Sound of Silence” and I suddenly got this impulse to write something down. I had no idea what the words would mean, and I just wrote them out quickly, a short feverish poem. I was 17, and I didn’t know what it meant or why I was writing it, but it was this impulse to create some ideas and put some thoughts out there. That poem is gone…but I always remember the feeling I had when writing it—expression, catharsis. Poetry is tremendous release for your emotions, for a cathartic release of important moments in your life. But it’s also a way of looking at the world and seeing the beauty, too. Sometimes I try to create the beauty of the world, or capture an amazing scene like a photograph would. “

In The Mapmaker’s Dream, Bill Meissner’s poetry is sometimes personal

sometimes objective, observational. “There’s a section on politics, about gun violence, suppression of freedom by powers, freedom of the press,” he tells me. “I have four different zones that I write from.”

His collection of poems is organized into four parts. “One zone focuses on significant childhood memories. A second area focuses on present-day observations, experiences, and/or relationships. A third zone is writing poems about unique characters; sometimes I write about invented, fictional characters, and other times I focus on American cultural icons such as Elvis, Harry Houdini, Marilyn Monroe, or Albert Einstein. And the fourth focus is poems that make a social comment.”

Part One: Drawing Lines With Glass Fingers, opens with the poem “The Mapmaker and His Woman.”

He should be working on his maps, but instead

he spends the day thinking that she is the distance between

point A and point B.

This seems to be about the things that occupy our time—the job, commitment, all the things we should be doing, the things we wish we could forget or leave. Meanwhile the things that get under our skin and into our brains, our preoccupations and obsessions, are the real subject, the reality most worthy of our attention:

When he stands and faces her, he realizes

what they have between them

is a map that, no matter where you follow it,

leads to the same place each time

…

Two people, standing on uncharted ground,

staring at each other, their eyes understanding

that they are the shortest distance between two points.

Recently retired from teaching creative writing at St. Cloud State University, Bill tells me he and his wife are doing a lot of traveling. And now that he has more time, he loves to meet any and all writers or poets in the area, of any age. To read some of their poems. To talk about poetry.

Bill Meissner Talks about Poetry

I wonder how we could interest more people in poetry, make it more fashionable. People who don’t know poetry, don’t know what they’re missing, I say.

“We could make t-shirts with quotes by T.S. Eliot on the back of them,” he says with a smirk. Then he has a better idea. “I have a student who tattooed two lines from one of Naomi Shihab Nye’s poem on herself—I don’t know where, I didn’t ask to see it. She loved the words so much, she had them tattooed on her.”

We could collect tattoo-able lines. Vital little poem-lines that work like mantras, to summon to mind whenever life seems too overwhelming or too hard. We could open a poetry tattoo parlor. Poetry, we agree, is that important. I ask Bill why it matters to him.

“You have to write for yourself,” he said. “It’s personal expression. You have to say what you think, what you feel, what you believe. What you hope, maybe. Or what you dream. So you have to do that first, and then hopefully it effects the world in some way, when people connect to your experience, what you’ve thought, dreamt. It is a work of connecting.”

But why is it important to express ourselves?

“It’s just a human urge, isn’t it? It’s the human compulsion,” Bill Meissner reminds me. “Nobody really wants to sit in a corner and face the wall and just stare at it. People ultimately need to connect. That’s part of a life, connecting with another human, or many humans. And the best writers connect with a large group of people and speak to them.

Bill Meissner explains what the best poets are doing, to make larger connections

“In poetry I would say that innovation is one thing, [having] something to say that’s not a cliché. Like Alan Ginsburg who speaks by saying something innovative about himself, about America. He articulates a social protest. So that’s the first thing, it’s innovative.

“For me, poetry also has to connect on a human level,” he explains. “Those are the poets I like best, you know, James Wright, Robert Bly, William Stafford, Naomi Shihab Nye… they connect on a human level and on an emotional level, too. I put Billy Collins in that list, too, for being poignant but also satirical, and tongue in cheek. There’s a humorous voice that comes out, which gives you a lighter side of looking at his life or his experience. And that’s positive.”

I, too. I think Billy Collins is a very relatable, readable poet. But I’m trying to get to the root of why, when poetry has this almost magical power to connect us, why do so many people react to the word poetry by shoving it away, by saying, ‘I don’t want that?’ Are people afraid to connect? Do they just want to keep it light, surface level?

Maybe people are afraid of poetry because they’re afraid of those deep feelings and deep connections. But why would anyone want to live a shallow life? I ask.

“I think in our culture, there’s a separatist attitude,” he says. “Separate this group from that group. Let this group be antagonistic toward that group. Exclude this group from our country. But I think people, especially forward thinking people, are hungry to connect with people. I’ve noticed that a lot more.”

Away from the attention of mass media, he tells me, there’s an undercurrent of Americans who are connecting with each other. They are not about forcing their politics or beliefs on anyone. or bullying people. They aren’t basing their identities on anti-this or pro-that, but they are connecting to resist what appears to be the status quo of separatist attitudes.

“I don’t know how large this movement is,” he says. “I don’t have any statistics, but I’ve noticed it. People are joining a group, stating a cause, creating some social change.”

Muriel Ruykeyser wrote about the power of poetry to work on human consciousness in a subversive, transformative way like nothing else does. And some people will say that all art does that, but not all art involves verbal language.

“Language is more direct,” Bill says.

Bill Meissner’s “The Mapmaker and His Woman”

And then he tells me about projects he’s involved in that connect poetry with visual art, music, and film. “Wayne Nelson is my video guru in Minneapolis,” he says. “I read a poem for him on a recording device, and he sets it to video. Then he sends it to another guy who puts music to it.” Wayne is a former student of Bill’s, who created this video of the poem “The Mapmaker and His Woman.”

How has poetry—reading, writing, teaching—made Bill Meissner’s life more meaningful?

“Good question,” he says. “It’s back to that idea of connecting. Poetry is a connector. If I do a reading or teach a class, and people respond to one of my poems, that’s awesome. And the other meaningful thing, for me, has been going into schools and sharing writing with students—high school, elementary, jr. high—and having students respond by writing their own kind of poem. I do as much of that as I can. I’ve visited classrooms at Apollo and Tech for an afternoon. I connect with them. Seeing people get inspired by your poem, and then being able to help them bring out their own unique language, that’s great. It’s not always a beautiful poem, but they try something for the first time in their lives, and then something amazing comes out. That’s a tremendous feeling, to inspire people that way.”

Writing poetry, Bill Meissner says, is a two-fold connection. First you connect your head to your heart. “You learn about yourself and what you feel. Flannery O’Connor said, ‘I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.’ So you learn about yourself by writing poetry, and the secondary element is conveying it to others., to help them create something, too.”

Our conversation leads us to the conclusion that one of the really important works of poetry is to draw out interesting stuff that we didn’t know was in us. But maybe all art does that. What makes poetry unique and distinct from other arts, I wonder.

“Every poem is a little capsule of life,” Bill says. “It encapsulates an emotion, an experience, a thought. And it’s often in one page, in 50 to 100 words. I think there’s a power in that. Poetry is very specific. Usually if you read a poem closely, you come to know an experience, and what the author felt like, and how you feel in reaction to the author. James Wright ended his poem, ‘A Blessing’ with the line: ‘Suddenly I realize that if I stepped out of my body, I would break into blossom.’ It’s that kind of epiphany, that kind of self-discovery that I’m talking about.”

Are you wondering whether, maybe, you might want to explore this poetry thing?

Bill Meissner’s introduction to writing poetry:

“I use a series of introductory assignments to spark creativity, little inspirational fire-starters, where they come up with an idea or metaphor and then expand it. I emphasize the building blocks of poetry—first image, then specific and concrete detail, then narration. I use a lot of examples by poets people can easily relate to: Naomi Shihab Nye, James Wright, about 10 different poets in a semester. Lucille Clifton, Billy Collins, Robert Bly, Denise Levertov. Sylvia Plath for the dark moments. I introduce them to all those master writers, including Alan Ginsberg’s poem ‘America’ at the end, to show them a poet who writes scathing social protest. And all of those things come together to give them a whole different perspective about what a poem can or might be.”

And how does Bill Meissner turn people into poetry readers?

I do that by picking really quality poems by famous writers. The ones that get anthologized. Where there are seemingly everyday experiences but they convey a significant insight, like William Stafford’s ‘Traveling Through the Dark,’ or Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Making a Fist.” In this childhood memory poem, she was sick and thought she was going to die with the flu, and her mother said, just to get her to shut up, ‘you know you aren’t going to die if you can still make a fist.'”

He tells me some students have written to him after ten or fifteen years, telling him they still remember that poem by James Wright, The Blessing. And they’ll quote the ending. He’s had people come up to him years after they left his classroom, and recite some lines from a poem he introduced them to, and they’ll say, “I’ve never forgotten these words.”

“Poetry gets under your skin,” Bill Meissner tells me, “And after it gets under your skin, it goes through the arteries to the important parts—the heart and the brain.”

And that’s how the poems we share connect us.

Bill Meissner’s The Mapmaker’s Dream is available from Finishing Line Press.

Bill’s precise language and lyrical voice create “poems that, with the eye of a novelist and the ear of a poet, reveal a world of intricate relationships.”

—John Minczeski

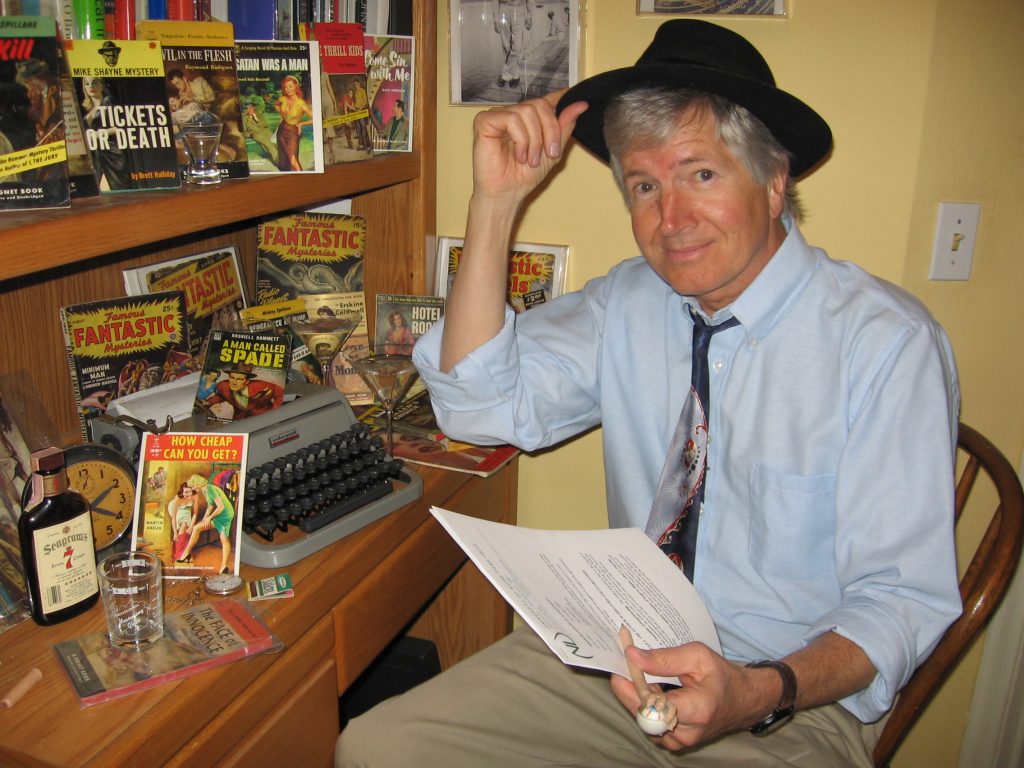

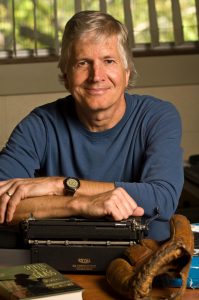

Author and teacher Bill Meissner

has published four previous collections of poetry: American Compass (U. of Notre Dame Press), Learning to Breathe Underwater and The Sleepwalker’s Son (Ohio U. Press) and Twin Sons of Different Mirrors (Milkweed Editions). His chapbook with a carnival/circus theme is The Glass Carnival (Paper Soul Press). He’s also the author of two books of short stories: Hitting into the Wind (Random House Publishers/SMU Press paperback/Dzanc Press ebook) and The Road to Cosmos (U. of Notre Dame Press). His first novel, Spirits in the Grass (U. of Notre Dame Press), was awarded the Midwest Book Award. Meissner is the recipient of several awards, including a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship, two Loft McKnight Fellowships in poetry and fiction, a Loft-McKnight Award of Distinction in Fiction, several PEN/NEA Syndicated Fiction Awards for short stories, and a Jerome Fellowship for travel/study in Mexico. His poems have been published and anthologized widely during the past years. Several poems included in The Mapmaker’s Dream have won awards, including “Song for the Refugees,” which was selected as a finalist in the 2018 International Poetry Competition, sponsored by The Atlanta Review.

Bill’s hobbies/interests include travel (especially to tropical locations), rock music, baseball, and photography. He also collects pulp fiction magazines, music memorabilia, and (too many) vintage typewriters. He has taught creative writing at St. Cloud State University, and, as a visiting writer, he frequently presents workshops at local elementary schools, high schools and colleges. He grew up in Iowa and Wisconsin, and lives in St. Cloud, Minnesota with his wife Christine.