“…questions, those caves in our knowledge

that pull us from light into deepest darkness…”

Mara Faulkner

from “Memoir’s Arrogant I/Eye and How to Teach It Humility”

How questions facilitate transformation

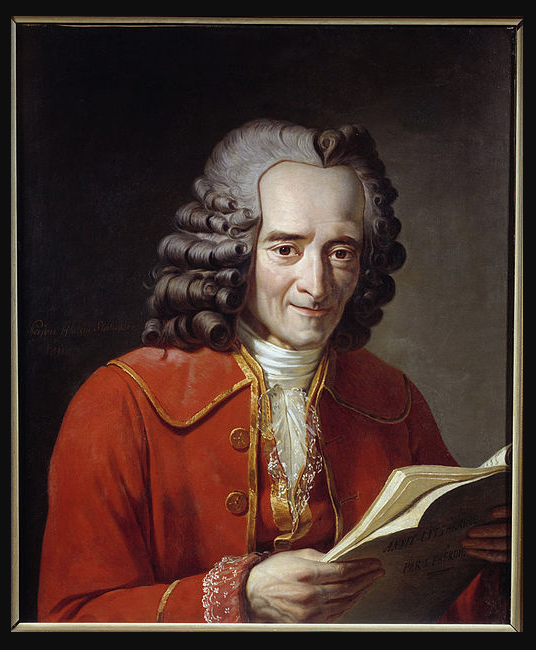

Voltaire was a court poet during the reign of Louis XV of France (ruled 1715-74). Although few people alive today have read his poems, “he continues to be held in worldwide repute as a courageous crusader against tyranny, bigotry, and cruelty.” Voltaire believed we should not judge people by the quality of their answers, but rather by the quality of their questions.

Tyranny, bigotry, and cruelty flourish when people normalize oppression and hatred, when they provide “reasonable” answers for why we should put up with despotic abuses of power. Answers repeat what is already known. Answers, as Voltaire recognized, justify our opinions and ideas, reinforcing political and ideological polarization.

Questions, however, probe possibilities and peer into the deepest darkness, the unknown. By illuminating what we don’t know, questions serve to stimulate the human imagination. Questions, by challenging the status quo, open individuals and societies to change, to grow, to recognize the truth of the matter. Only when we know what is true, what is really happening in us, to us, and around us, can we respond in a way that is helpful and good. In other words, questions facilitate transformation.

Questions test ideas

Mara Faulkner is a poet, literature and writing instructor, and author of the book Going Blind: A Memoir. Despite its title, Going Blind is, as Mara says, “more like a collection of essays which begin with questions, those caves in our knowledge that pull us from light into deepest darkness. I’m speaking here …of the classical definition of the essay, whose name comes from the French word essayer: to try, or test, or assay an idea as one tests raw ore for precious metal.”

Albert Einstein explained why asking imaginative questions is superior to providing answers. “Imagination,” he said, “is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.”

In her essay “Memoir’s Arrogant I/Eye and How to Teach It Humility,” Mara Faulkner questions the purpose of writing and publishing contemporary memoir, which, she says, appears to be “settling into some drearily familiar patterns…of trauma and disaster.” In recognizing these patterns, she asks, “What happens to ordinary lives and quiet survival in the wake of this flood of memoirs of trauma and tragedy?” Do they, too, become unbelievable, or, worse yet, uninteresting?

These are important, even necessary questions. If I don’t question what makes a human life truly interesting and worth living, what are the chances I’ll enjoy an interesting, worthwhile birth-to-death journey?

What makes a question real?

Mara Faulkner is a professed member of Saint Benedict’s Monastery, a community of Benedictine sisters who live quiet, simple lives. Theirs is a history, she tells me, of doing “pretty much ordinary stuff. I mean teaching is ordinary. Nursing is ordinary. Taking care of old people is ordinary, and not many people even want to do it. Working in parishes is ordinary. None of it is spectacular in any way.”

I asked her whether living a monastic life, with an emphasis on a daily routine of work and prayer, gives her a sense of completeness, as in having found the answer to what makes life worthwhile.

No, she said, rather, it gives her a sense of incompleteness. “I don’t want completeness. I really don’t, because then I think I will have stopped asking questions. And I never want to do that. If I thought monastic life gave us all the answers, that would feel like death to me.”

And yet so much of our culture is built on the certainty of having all the answers. So living a questioning life is countercultural.

“I never think of it that way,” she said, “but I guess it is.”

Teaching, she said, is what led her to questioning. “The thing is, students don’t believe that any of their teachers’ questions are real. They think that when I walk into a class and ask something, I’m just fishing for the answer that I want. And for a long time, I think I was doing that, and I think lots of teachers do. But then I thought, ‘What would happen if I asked a real question?’”

A real question, she explained, is one we don’t know the answer to, one that causes us to want to hear what other people have to say.

And that became her teaching practice. “The whole of it, to walk into every class, every day, with a few questions to which I don’t know the answer. These questions matter to me, but I’m not fishing for the right answer but for the variety of answers my students might offer. Because then what happens, is that I learn from my students.”

Mara recently led a writing workshop called “From Grief to Grace to Gratitude to Gift.” People who signed up for the workshop had a big grief to write about, like enduring abuse, or the senseless death of children. She encouraged participants to put the story of their grief on paper, but that was only the first step. Then she pressed them to ask questions and to think, “How can ,that grief become a grace? And is there anything in it that I can be grateful for? And then finally, is there anything in it that I can offer as a gift to other people?”

Revenge, she says, is never a worthy reason to write anything.

The question of humility

What Mara Faulkner is really talking about when she’s talking about questioning our assumptions and motives is an antiquarian concept of how to be human, excavated from ancient cultures. Humility is something we’ve mostly lost in our society, but not entirely. The New York Times recently published the article “Be Humble and Proudly, Psychologists Say,” which explains that humility is “a valuable facet of personality. A humble disposition can be critical to sustaining a committed relationship. It may also nourish mental health more broadly, providing a psychological resource to shake off grudges, suffer fools patiently and forgive oneself.” That’s why psychologists are studying humility, exploring whether it is an innate a personality trait, or if it can be taught. They’ve found that “between 10 and 15 percent of adults [in the United States] score highly on measures of humility.”

Worldwide, there are approximately 46,000 Benedictine monks, sisters, and oblates (people associated with, but not living in, a particular Benedictine monastery). Benedictines have been teaching humility to their community members for nearly 1,600 years. And in all of her writing classes, Mara Faulkner, OSB (Order of Saint Benedict) teaches her students the humble practice of asking questions. Because if you’re not asking real questions, she says, discussion—the free and fruitful exchange of ideas– will not happen.

And when a writer knows all the answers, the writing tends to sound like a lot of shouting.

But people don’t generally like questions without answers. Does that mean they don’t like to discuss?

“It means they don’t like questions,” she said. “Because a question, by definition, is something you don’t know the answer to. If you know the answer to what you’re asking, it’s a statement with a question mark at the end, and that’s all it is.”

Admitting that we don’t know is the essence of humility. And yet, paradoxically, humility does not make us wishy-washy. Instead, humility is associated with people who are most able to hold on to their convictions. In the NYT article about humility, one researcher reported that “people high in intellectual humility are not easily manipulated with regard to their views.”

And yet paradoxically, “Those who scored highly on humility — not that they’d boast about it — also scored lower on measures of political and ideological polarization, whether conservative or liberal…[and] people who score high for humility are less aggressive and less judgmental toward members of other religious groups than are less-humble people, even and especially after being challenged about their own religious views.”

Is it possible, then, that if we humble ourselves to ask meaningful questions, and listen to other people’s answers, we could break down the political and ideological polarization in this country? Is that how we might begin solving our problems? Could it be that simple?

The poetry of questions

Simple, perhaps. But what is simple is rarely easy. To facilitate discussion requires strenuous, thoughtful effort toward an unpredictable outcome. It is like writing an essay, which Mara Faulkner says, “is an attempt that may or may not be successful. It is strenuous. In thinking and writing, the essayist meets resistance from the recalcitrant ore, reluctant to give up its gold.”

Bill Moyers recently asked this question: “So how is it that we are living in what is arguably the safest time in history, yet we as a country exist in a culture of fear?”

Some might say the thing we are most afraid of, is questioning our own ideas. And now I’m wondering whether all of our cherished ideological opinions are actually excessively uninteresting, while authentic, meaningful questions are what make a life infinitely fascinating.

So what do you think will break our wild fear of questions? I think this poem is a good place to start:

This Poem is Nothing but Questions

Mara Faulkner

When I saw the dream buffalo charging toward me across the

trembling earth, why did I cower, my arms over my head?

Why did I shake so hard the whole bed shook with me?

Why didn’t I turn to face them to see if they would part like dark

waves on the right and on the left?

If they had trampled me, what gift would I have received from

death?

Why did the man, roused by my screams, come and shoot the

buffalo? Why did he brag, “Now you have some trophies”?

Why were the trophies the brown furry heads of bears?

Why did I, with my fear, my shaking, turn the man into a killer

here where courage is the only virtue that matters and cowardice,

not cruelty, the unforgivable sin?

Why did I wake up sick with complicity, though I hadn’t fired a

shot? Why don’t I know if I, the woman, am guilty of cowardice

or of courage?

Why am I afraid to admit that I am the buffalo and the bears, all

dead, the trembling earth, and the man, with his necklace of

skulls?

What knowledge, rising in dark waves on the right and on the

left, do my fears prevent?