Our aching hearts are finally soothing

Enough all wars brewing

The truce is blooming

like petals hither and thither…

–Abdi Mahad, from “Peaceful Breeze”

Between 1953 and 1985, the American Black Mountain poets Denise Levertov, from Manhattan and Mexico, and Robert Duncan, from San Fransisco and Stinson Beach, exchanged over 450 letters. Commenting on The Letters of Robert Duncan and Denise Levertov, Adrienne Rich writes, “in these letters, two distinctive artists tried — beyond gender, sexual orientation, politics — to work out, with and against one another, the values and processes of their art.” They shared a poetic dialogue in which, “the letters become a kind of embraced wrestling, not just with one another but with passions, beliefs and vulnerabilities within themselves.”

Abdi Mahad and Hudda Ibrahim

Abdi Mahad is a poet, editor, and instructor who now teaches English at Tech High School. Apart from his teaching, Abdi provides training sessions and translates employee handbooks, orientation, and good manufacturing practices into Somali. He also offers on-the-job American work ethics for immigrant and refugee employees. His wife, Hudda Ibrahim, is the author of From Somalia to Snow: How Central Minnesota Became Home to Somalis. As the founder and president of Filsan Talent Partners and faculty member of St. Cloud Technical and Community Colleges, she specializes in topics of diversity and inclusion, cultural competency, and women’s leadership. Recently I met with the two of them to dialogue about poetry, a love the three of us share in common.

Abdi has been reading English poetry for most of his life, since before he could make sense of the words. He began writing poetry when he was 14. “About the time I left my country, I would always sit down and try to write down my own experience about fleeing that home, fighting I saw, people being killed.” Although his English was not yet fluent at that time, he chose to write in English. He is working on a collection of poems chronicling his experiences, “Starting from the conflict in Somalia, and coming to the United States, where everything is new, the weather, snow, the food.” His passion for English poetry developed through reading Shakespeare. “Now I’m in love with poetry,” he said.

We talked about how poetry can do the work of holistic healing. After the trauma of fleeing your country because of war, leaving your home not because you want to, but to save your life and the lives of your family members, Abdi said, “Sometimes there is a flashback, you remember what happened, especially when you watch a violent movie, you say, ‘I don’t want to watch this movie,’ because it removes the scab of the wound, you remember the pain, it all hits you.”

There is something inherent in the beauty of poetry that allows us to examine, accept, and live with the pain. “Hudda can talk about that,” Abdi told me. “She has written a lot about healing and forgiveness.”

On Embodied History

Forgiveness is an important part of healing after trauma, but it’s difficult work. “You have to have the right, safe environment for people to come and choose to talk about those things, especially trauma. People can break down in the middle of discussions.” It has happened at the Dine and Dialogue events Hudda and Abdi host in Saint Cloud, where the sharing of food and discussion brings together people of different faiths and cultures to increase understanding and promote harmony. In this environment, people feel safe telling their stories, and sometimes people cry. The community is there to support them.

We discussed how poetry and song might connect people in ways that support diversity in the building of community. Hudda wants Abdi to share his poetry with the community. “Abdi, he is a writer,” she said. “I know he is a writer. He has been writing since he was 14 years old.” Through his poetry, Abdi could tell of the beauty of Somalia before war ravaged the country and its people. “Many people only know Somalia as it was after we had the civil war. Somalia was beautiful. Life was beautiful. But the thing is, the people who are born either at that time or after the civil war, when people fled from Somalia—they know nothing about Somalia. They only remember their families talking about it.”

She had just received an email from a young woman who is in high school, saying that she had read From Somalia to Snow, and she learned about her own culture.

A similar thing happens to Abdi, too, teaching English to Somali students. They will tell him their parents never talk about fleeing the country, or what it was like in Somalia. It’s difficult to talk about trauma and loss. But Abdi spent many hours of his teen years writing about those times. Here’s an excerpt from poem he wrote when he was 15:

Why is the war?

Abdi Mahad

Why is the war? Why is the hate?

How many died from shelling,

bodies blown to smithereens?

How many died of hunger?

Bodies left parching

withering in the scorching sun.

How many died at sea,

Bodies washed to the shore,

Bodies buried unwept?

None had graves, no epitaphs seen,

No proper procession

No proper burial conducted.

I asked whether writing about the trauma changed anything for him. He described writing as a way of transforming pain by letting go of the past. “This happened to us, to all Somali villages. When you come here, your family is safe, and then you just put all those pieces together and start from fresh. That’s what we did.”

Abdi and Hudda have known each other for more than five years. They married two years ago, after Hudda completed her education. At the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University, Hudda majored in conflict resolution and English literature. She holds a master’s in conflict resolution from the University of Notre dame. Abdi has a bachelor degree in Business Management and a master’s in Teaching English as a Second Language. He also has some of other degrees in computer science.

The Poetry of Somali

Hudda sees Abdi’s writing as a tool for education. “For people who might not know anything about Somalis and the civil war. I would like to see Somali people writing about pre-civil war, to help others understand that the country was a peaceful and beautiful, and prosperous country. But because the wars happened, that’s why we’re here. I think that’s where Abdi could do a good job of presenting Somalia. Somalia is the land of poetry.”

She told me the story of Hawo Tako, the Somali nationalist and poet. “She was among the women who fought in the Italian invasion.” Hawo is Eve, Adam’s wife in Judeo-Christian mythology: the first woman and mother of the human race.

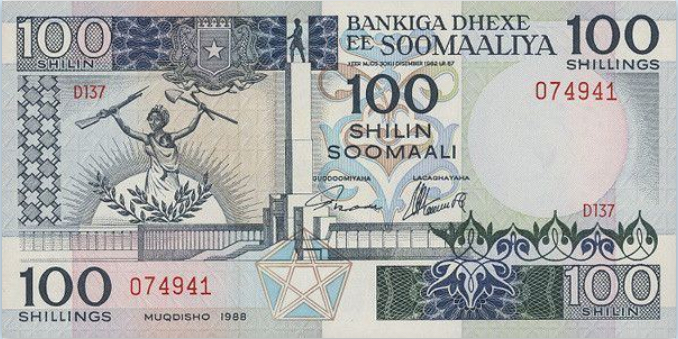

There is a statue of the poet-warrior, Hawo Tako, in Mogadishu, and her image is on Somali currency, on the 100 Shilling note. Her poetry encouraged Somali people to defend their nation from invaders. Hudda explained that as an editor for a Somali newspaper based in Minneapolis, she wrote about “how women were a part of the movement to decolonize Somalia, before the ’60’s. We took our independence in 1960, from the Italians.”

In 1948 Howa Tako was leading that movement, Abdi said, “She was leading men, and reciting poetry.”

“Every Somali that you see walking down the street could recite poetry without even thinking about it,” Hudda explained. “We’re walking poets. People just open their mouth and…” Her face shows amazed rapture, as if she is listening to the whispers of angels, “they speak poetry.”

“My grandfather was a poet,” she said. “My grandmother who is now 90-plus, every time we talk to her over the phone—she’s in San Diego—she speaks to us in poetry…. There are a lot of Somalis who will tell you Somalia is the land of poetry. Women! Women also have a tradition of poetry.”

Poetry as a Stage for Dialogue

“Somali women’s poetry is different from the men’s poetry, in style,” Abdi said.

Hudda explained, “Women usually write about their perspectives, because of sexism, because of patriarchy. And men tend to write about how they are powerful, either in the government or colonization, but women weren’t a part of that.”

Abdi added that he loves women’s poetry, as it tells about everything about the life of a woman. What I like about women’s poetry known as “Buranbur” in Somali is that it has alliteration pattern and stanza that resemble Old English poetry

Hudda said, “With Somali poets, the poetry springs from the life lived.” Somali poets speak their embodied story—their personal history and the history of their people—in the form of poetry. But Somali poetry is also often inspired by beauty.”

“They are all of them, men and women,” Abdi said, “writing about nature. Beautiful nature.”

I asked whether men and women poets listen to each other, or if they are separate cultures within a culture.

“They do both,” Hudda said. “There was a guy, a male poet, said some nasty things about the women. So then this woman, what she did, was, she replied to him. In the form of a poem. And she talked about how, in the past, Somali men used to honor women. And respect women. And how that changed over the years, and oh—I used to listen to that poet and think, ‘Go girl!’ Some men insult people and expect a woman may not reply to them. I’m not generalizing all Somali men here, but that particular guy, held power within the community. It’s like so-called religious leaders sometimes may say weird things about women, because they have the power, the platform to influence others, and they think no one’s going to come after them. We are now westernized, educated, highly intellectual women who will come after them and say, “Wait a minute. That’s not what the Koran said, or what God said. I think you’re misinterpreting. Maybe you’re basing your opinion on your own interpretation of this. So, let’s talk about this, have a platform.” Now we have highly educated, intellectual Somali women who are saying, “No. You will recite poetry? We will recite poetry, too!”

And so poetry has become a stage for a dialogue between Somali men and women. We agreed that it could also be a stage for dialogue between cultures here in central Minnesota, as it has been for the three of us, talking about poetry and discovering a shared love for beauty, with shared dreams for peace and unity.

Here is the last stanza of the poem “Why is the war,” which Abdi Mahad wrote in his teens, in the early 1990:

United we stand, divided we fall.

Let’s put aside our difference,

Let’s stand proud, heads held up high.

Let’s stand tall with hand over heart.

Let’s stand united, hand in hand.

Let’s stand together shoulder to shoulder.

United we’ll achieve great goals, divided we shall fall!

Let’s put aside our hatred once and for all.

And here is a poem he has recently written:

Imagine

Abdi Mahad

Imagine there is one race

Nothing to kill

And no one to discriminate

And no class that separates us

Before we tread down on a perilous path

Fraught with trepidation and anguish

Before we perish

Before the earth devours our body parts

Let us make earth better