Welcome to Sunday Morning Lyricality, featuring a weekly song or poem by a Minnesota writer, followed by a prompt to help you write your own poem.

Dr. Dorothee Ischler of the Center for Healing and Resilience in Northfield, MN says that validation “can be a practice that will help us bridge our differences. We come from different backgrounds and have various experiences and personalities that invariably will lead to a different perception of reality. Validation implies that each of us has the right to perceive things differently and that each reality is valid. It doesn’t imply agreement. In that way, it is akin to tolerance but it’s more explicit than tolerance. In validating someone, we are saying, ‘I understand that you feel this way, and coming from your experience I would probably feel the same way. I hear the sincere longing in your heart. I hear how strongly you feel about it. Your feelings make sense to me, even though I feel differently and have different goals.'”

“Egg Money” is a poem of validation. It gives voice to a historically marginalized woman’s experience, that of a late 19th century agricultural entrepreneur in Barnes County, North Dakota. Validation happens when we open our hearts and minds to listen compassionately to another human’s story.

May we all learn to use validation to bridge our differences.

Tracy Rittmueller

Egg Money

KateLynn Hibbard

Barnes County, North Dakota, 1893

When I was to be married

my brother gave me

a small flock of laying hens,

six biddies

and a Rhode Island Red rooster.

By the next year

I was raising seventy-five chicks

such a ruckus of chirping

when I brought around pans

of water and mash!

I kept them in the kindling box

next to the cook stove

until they were old enough

to live outside,

prayed they would escape

the marauding fox.

Well, enough of them did,

and in two years’ time

I walked fourteen miles

to town with a crate full of eggs

on my back, paying

for sugar and salt,

coffee and kerosene,

and I could sell a broiler

for 25 cents, got 50 cents a piece

for laying hens,

but when the government man

came through and drew up his report

on the work

done on our farm,

there was no name but my husband’s–

“wheat farmer” it said

for occupation–

no mention of the stacked eggs

packed in straw,

feathered carnage by the back shed,

no name for the plucking,

the singeing of skin

to ease out the feathers,

no word for my labor but wife.

Mother. Helpmeet.

*****

Visit KateLynn Hibbard’s website, where her bio reads: “KateLynn Hibbard’s first book of poems, Sleeping Upside Down (Silverfish Press 2006), won the Gerald Cable Book Award. Her second collection, Sweet Weight, was released by Tiger Bark Press in 2012. She is editor of When We Become Weavers: Queer Female Poets on the Midwest Experience (Squares & Rebels Press, 2012). Other honors include the Aestrea Foundation’s Lesbian Writing Finalist Award, a McKnight Artist Fellowship in Poetry, two Minnesota State Arts Board Initiative Grants, a Jerome Foundation Travel Grant, and residencies at Hedgebrook and the Cornucopia Arts Council. A long-time singer with One Voice, Minnesota’s LGBTQA mixed chorus, and a professor of writing and women’s history at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, she lives with many pets and her spouse Jan in Saint Paul.”

Writing Prompt based on “Egg Money” by KateLynn Hibbard

We offer writing prompts based on featured poems for people who want to write something, who need a little help getting started. We certainly don’t want to imply that you ought to write something. Many people enjoy reading or listening to poems without feeling compelled to write one. You might simply read this prompt as a deeper exploration into what the featured poem is doing, and how its language works.

Want to write your own poem of validation?

Are you wondering how to write a poem to give voice to the experience of a marginalized person?

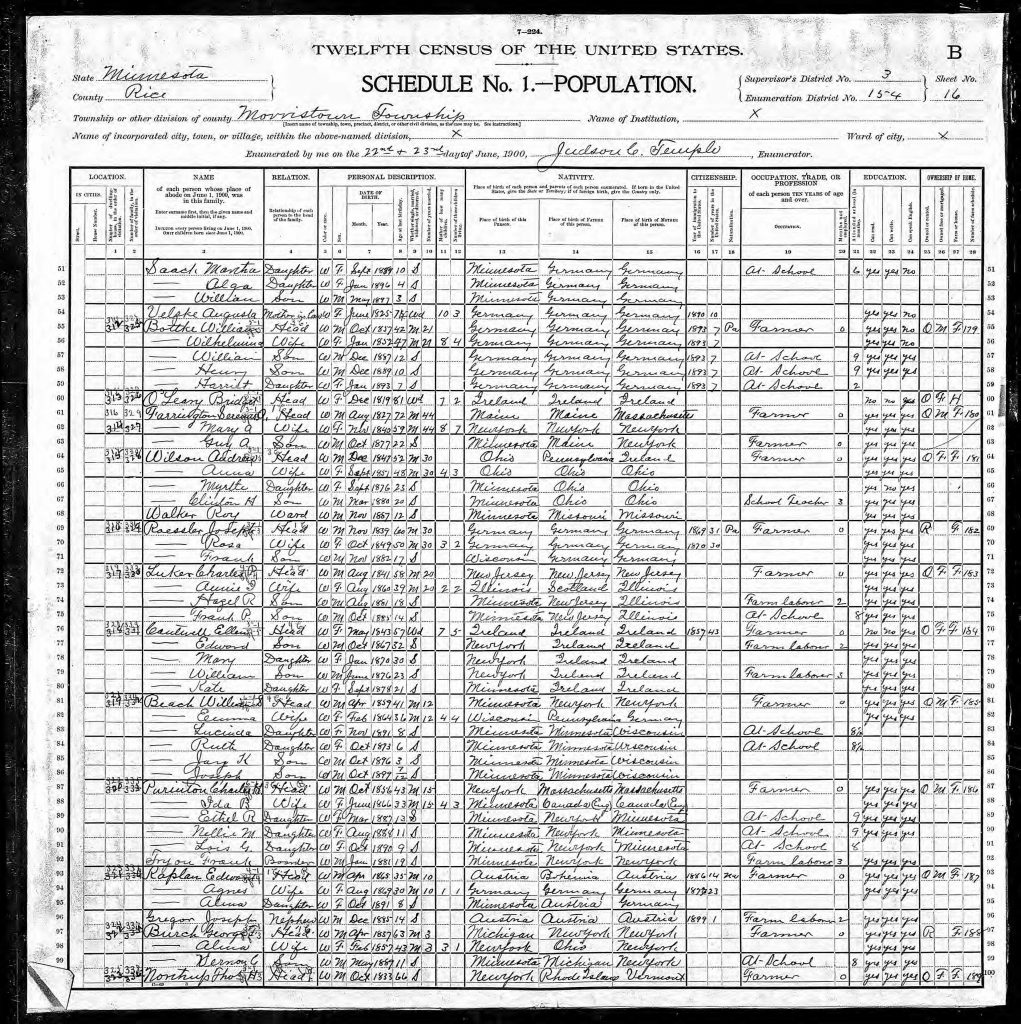

Historians and genealogists may recognize the inspiration for this poem–a government “report / of the work done / on [a] farm.” These government reports were meant to insure compliance with the colonizing Homestead Act, and were used to determine rights of ownership.

Notice how KateLynn begins with a place, Barnes County, North Dakota, and a time, 1893. She writes in the voice of a woman considering that record, whose occupation was unmentioned, who tells her story in the form of a complaint or lament. Notice also this poet’s use of prepositions and conjunctions to move the speaker’s story to its hinge point. Moving through the poem line by line feels a little bit like watching a door opening into this woman’s accomplishment, but then it closes again after the plot twisting line, “there was no name but my husband’s.” After a small peek into this woman’s life, the poet shows us the erasure of her unique individuality, never naming her, but identifying her only in abstract terms–“wife. / Mother. Helpmeet.”

To write your own poem of validation, first, don’t write on behalf living people. Instead, find a way to empower them to tell their own story, like Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop does. You can turn to the past, which is full of the unrecorded stories of marginalized people due to indifference and erasure. You can write on behalf of a person who was very much like you, whose death prevents them from telling an important story.

If you’re from a dominant cultural group (in the United States, if you are white), you will want to avoid getting into the racist territory of insensitive cultural appropriation by following KateLynn Hibbard’s example. Choose an ancestor, or someone very much like one of your ancestors, someone you might have been if you had been born in that time. Locate a moment of indifference or erasure and name it from your chosen person’s perspective. Examples might be, “They told me never to speak of it,” “my pain was inconvenient for them,” or “my achievement was too bold for my station in life.” Then simply write the story that you know (or imagine) should have been recognized and validated. Be sure to name specific accomplishments, for example, “seventy-five chicks” and “a crate full of eggs… /… paying / for sugar and salt, coffee and kerosene”. Next, jot down an observation, from your character’s point of view, about what should have happened. In this poem, the character might have said, “They should have validated my contribution by naming it.” Finally, write for your character what it would have looked like, if validation had occurred.

In revising, shape the story into lines. Begin with the word “when,” and start each following stanza with a conjunction or preposition–(such as by, well, and, but–to clue the reader that you are telling a story. Include details. You might do a little historical research to surround the story with artifacts of the time like KateLynn does when she mentions “I could sell a broiler / for 25 cents, got 50 cents a piece / for laying hens,”. Insert the moment of erasure, and then tell what should have happened, but didn’t.

Consider the way KateLynn condenses the idea of “this should have happened but didn’t,” into the repeated word “no.” Also consider that she could have ended her poem with the word, “wife.” By choosing to instead add two more generic expectations and limitations for women’s identities throughout history, the poem gains power.

For your final revision, consider where you might condense, and/or where you might expand one or two key concepts.

*****

“Egg Money” from Simples ©2018 by KateLynn Hibbard, published by Howling Bird Press. Appears with the permission of the author.